Havana, Cuba: At dawn on July 26, 1953, armed youths heard the plan for the first time: they would attack Cuba’s second military fortress to restart the war, there would be 120 against a thousand and they depended on the surprise factor.

The leader Fidel Castro was driving the second of the 16 cars, his right hand on the wheel held the pistol while his left held the 12-gauge shotgun, in his mind he was reviewing a project of months.

From the apartment on 25 y O streets in Havana, he and Abel Santamaría had devised the attack on the Guillermón Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba and Carlos Manuel de Céspedes in Bayamo (east), to later start the war in the mountains and overthrow the coup d’état (1952) of Fulgencio Batista.

Of the 1,200 men organized in cells, 160 youths were chosen for the action and traveled from the west some 48 hours before the appointed day, 120 would attack in Santiago and 40 would go against the other garrison.

Haydee Santamaría and Melba Hernández, the only women involved, brought dozens of weapons with them by rail and everything was about to be discovered when soldiers at the train station offered to carry the heavy trunks.

This is confirmed by historical research and the count of the survivors of that armed action for which the country commemorates the National Rebellion Day.

Around 4:45 in the morning local time, the assailants left the meeting point at the Siboney farm; it was Carnival Sunday so as not to attract attention, three groups of cars separated in the vicinity of the Moncada.

The first under the command of Abel Santamaría would occupy the Civil Hospital that adjoined the fortress; the second, in which Raúl Castro participated, would seize the Palace of Justice, a tall building from which they would support the main action; and the third group, with 90 members commanded by Fidel Castro, would take over the headquarters of the barracks.

They were dressed as sergeants to create confusion, the revolutionaries could recognize each other by shoes and weapons that were different from those of the Army.

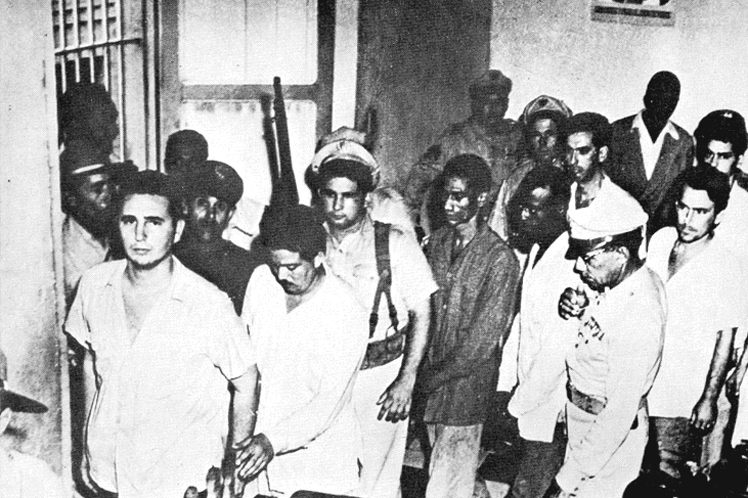

An unanticipated guard unleashed a skirmish, shots were fired and the Moncada alarm alerted the rest: the surprise factor had been lost, after an unequal combat it was necessary to retreat.

Batista ordered the killing of 10 revolutionaries for each soldier killed in that action, eliminated constitutional guarantees throughout the national territory and applied censorship to the press and radio.

Abel Santamaría was tortured and assassinated, like many of the attackers, a situation later denounced by Fidel Castro during his intervention before the court that tried him.

The self-defense plea of ??the then young lawyer, later known as History will Absolve me, pointed out the hardships of the people under that Republic and advanced the social programs that the triumphant Revolution would then apply in 1959.

After the prison in the former Isla de Pinos, an amnesty by popular pressure allowed the assailants to travel into exile and prepare an expedition that would return with 82 men to start the irregular war in the mountains of the Sierra Maestra (east).

Researchers coincide in pointing out the political significance of the actions of July 26, which were also a tribute to the ideas of the Apostle José Martí on the centenary of his birth.

The people of the island celebrate on this day the date under the slogan My Moncada is today, a call to defend the socialist project from home, work or social networks in the era of the soft coup against Cuba.